As expected in my last update, infections soared in Romania over the month of October, reaching as high as around 19.000 a day in the middle of the month, and a total of almost 415.000 for the entire month. Following a similar pattern with other Delta waves around the globe, new cases started decreasing afterwards almost as fast as they were rising before, despite few extra restrictions – you may attribute this pattern to some inherent property of Delta or to the complicated transmission dynamics in a networked population. Personally, I continue to think that school closures contributed significantly to reducing transmission.

The decline continued until the week between Christmas and New Year, when cases started rising again, almost explosively: we went from a weekly average of 650 before Christmas to 1.220 after, an almost 90% increase, and this week the trend accelerated, surpassing 6.000 cases yesterday. This could be an effect of winter holidays, combining less testing with more social mingling, but I fear that it’s in fact the start of our Omicron wave. At this growth rate, we may well reach and surpass the previous record by the end of January – or sooner… Officially, the number of confirmed Omicron infections in Romania remains low, with 91 cases confirmed on January 5th (for a total of 183 so far), but worryingly over half of these 91 cases (51) are in vaccinated people.

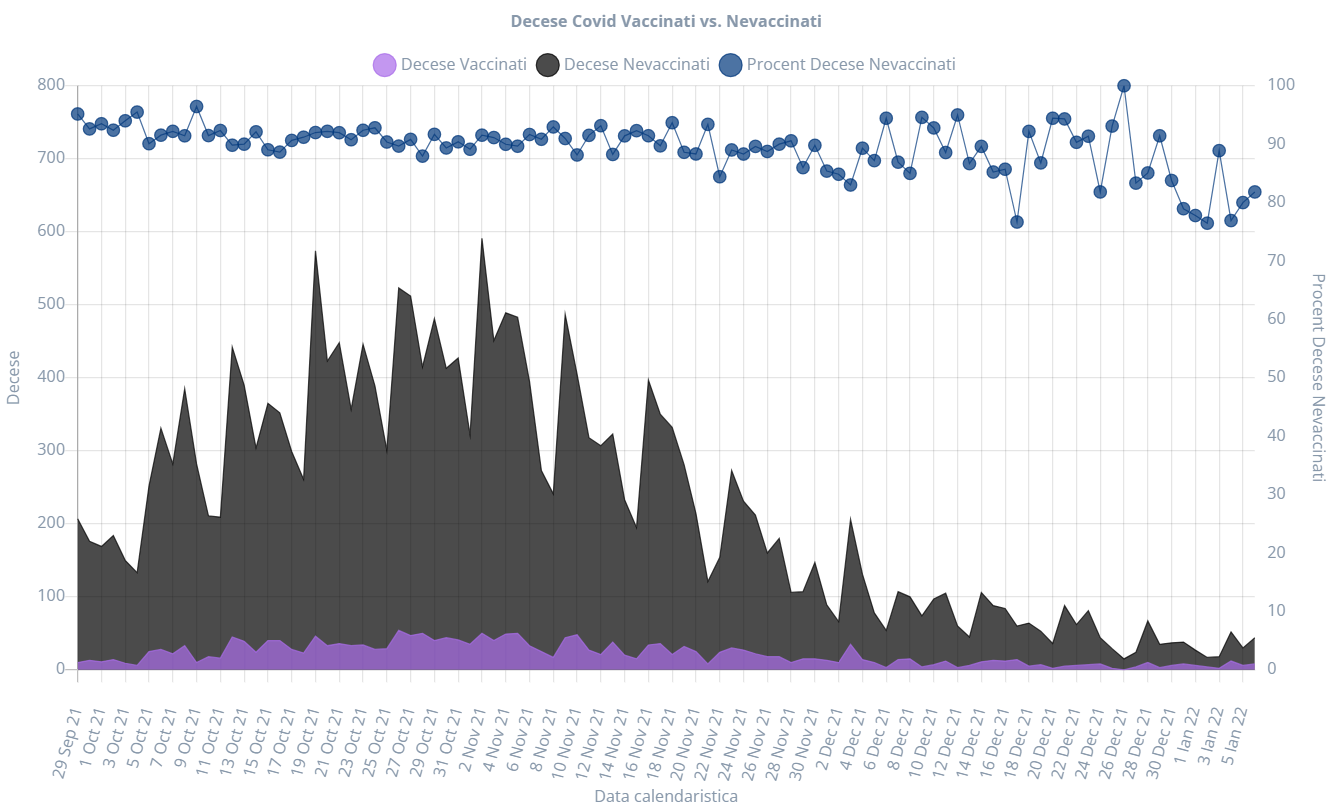

As before, deaths have trailed the progression of infections by two–three weeks, reaching daily highs of almost 600 in the latter half of October and first half of November, and have been consistently declining since. Important to note that over these past months an overwhelming majority of deaths (about 90%) were among the unvaccinated. The pattern is confirmed by data on ICU patients, where also less than 10% are vaccinated. Considering the issues with fake vaccination certificates, that number may be lower still. Post-vaccination infections have also been very rare: according to a report from October, only 1.3% of fully vaccinated people in Romania have subsequently tested positive for COVID-19. A clear indication that vaccines indeed protect people from hospitalization and death – for those who care to look at and trust the data…

Speaking of vaccines, the status in Romania continues to remain disappointing. During this autumn wave we saw a surge of vaccinations, with a peak as high as 111.000 daily first doses in the last week of October, distributed just about equally between Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. Unfortunately, as soon as infections peaked and authorities started backpedaling on the use of vaccination certificates, interest in vaccinations quickly waned, decreasing to a measly level of a couple of thousands first doses daily. It’s dismaying to see so many treating vaccinations almost like a magic talisman to keep the disease away: rushing to get one when infections are high and ignoring them when the danger seemingly subsides.

The latest figures put the vaccination percentage a bit above 40% of the population. On a more positive note, people are at least conscientiously returning for their second dose in case of mRNA vaccines. Compared to initial inoculations, general interest in booster doses looks more consistent over time, staying around 20.000 daily doses for the first months after they became available – although these numbers have also declined steadily during December. Overall, almost 35% of the people with mRNA vaccines have also received their third dose.

Elsewhere around the world, the big news of the past few months has been the emergence and rapid spread of yet another viral mutation. First identified in South Africa and provisionally labeled ν, it quickly found its way into other countries, possibly before being formally identified. The WHO promptly stepped in, not with any useful advice or action, but to rebrand the variant away from this Greek letter, which sounds too much like the English ‘new’, and from the next Greek letter, which might have offended a certain leader of the country which started this whole ordeal, thus landing upon Omicron. If its handling of this pandemic so far hasn’t done enough to discredit the WHO, this pathetic political correctness exercise only contributes to its irrelevancy.

A WHO source confirmed the letters Nu and Xi of the Greek alphabet had been deliberately avoided. Nu had been skipped to avoid confusion with the word "new" and Xi had been skipped to "avoid stigmatising a region", they said.

— Paul Nuki (@PaulNuki) November 26, 2021

All pandemics inherently political!

Surprisingly enough, many governments reacted promptly this time around, introducing restrictions against travel from several African countries. This though prompted a wave of whining and protests on social media, repeating the baseless argument that travel bans don’t work (hmm, I wonder how China, Vietnam, New Zealand, and Australia managed to keep the virus at bay for so long?!), and accusing officials of racism and trying to undermine African economies (if your economy relies on tourism almost two years into a pandemic, you’re doing something wrong). Media likes to highlight the rightwing resistance to public health measures, from opposing masks and lockdowns to spreading misinformation about vaccines, but this to me is an example of a leftwing agenda used against measures with little scientific basis. With anyone and everyone finding excuses to push against common, concerted actions, is there any wonder we’re nowhere closer to ending the pandemic than early last year?

The whole discussion served to underline, yet again, why travel restrictions aren’t working in the real world: they’re inconsistent, have too many loopholes, and are rarely enforced properly. In the UK for example, travel restrictions meant testing more people arriving from Africa at the airport and then… letting them walk away on the promise that they’re going to isolate if they test positive. I still hold the unpopular opinion that most travel should have been halted indefinitely, except for freight, until transmission was under control globally. Then again, that would have deprived hordes of people of their sole meaning in life: boasting about their travel pics on Instagram…

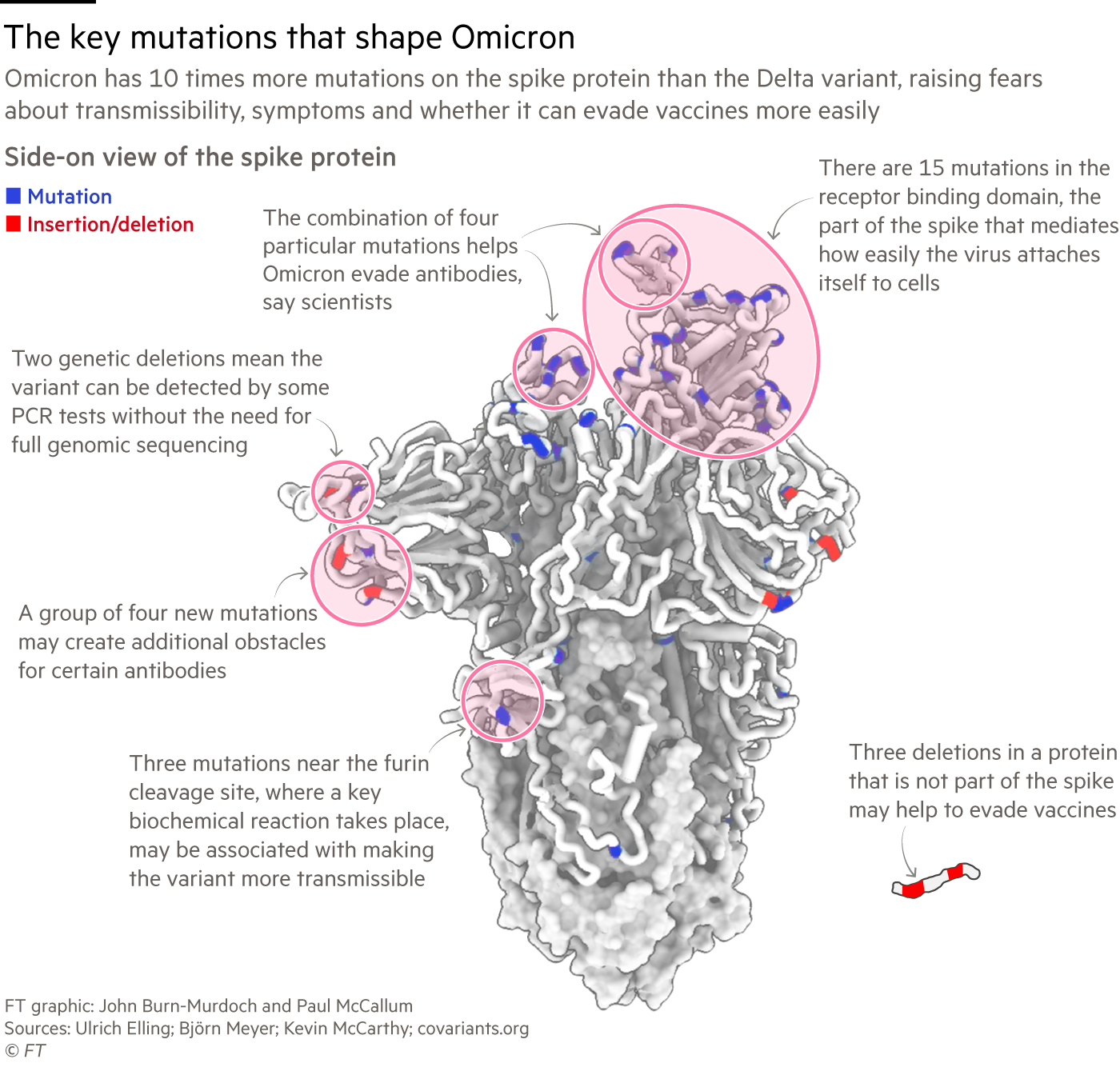

Since Omicron was identified, scientists have worked to determine the properties of the new variant, if existing vaccines still provide sufficient protection, and how concerning it should be for the future evolution of the pandemic. Genetic sequencing already showed numerous mutations in its RNA structure, many more than either of the previous variants accumulated. Early indications from South Africa pointed to an even more contagious strain than Delta but causing less severe symptoms. More recent studies in Denmark and the UK seemed to confirm this. Unfortunately, this late into the pandemic it becomes increasingly hard to extrapolate studies performed in one region to others, because of many variances accumulated over time: beside the inherit demographic differences (South Africa has a much younger population than European countries), populations now have varying levels of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 stemming from either vaccination or prior infections, immunity which also varies depending on what types of vaccines were administered, how long ago and if they were followed up by boosters, and on the viral strains that were prevalent (South Africa experienced waves with the Alpha, Beta and Delta variants, while Beta never became widespread in Europe and Americas). With our low vaccination coverage, I doubt Romania will fare particularly well when Omicron inevitably hits…

Another crucial aspect is the age distribution of disease. Several reports indicate that Omicron is increasingly infecting and putting children in hospitals, but it’s hard to say if this is a consequence of the viral mutation or of the low vaccination coverage in children. As Omicron spreads further, it’s possible it will start affecting older populations yet again.

On the efficacy of vaccines, several studies showed that omicron more easily evades antibodies from either prior infections or vaccination, and that the best protection would be a third mRNA dose – unfortunately, it’s not clear how long the protection from the booster dose would last… On a more optimistic note, immune protection from T cells looks much stronger even following the standard two-dose regimen. I think the high number of mutations and immune escape make a stronger case for updating mRNA vaccines to target this variant or creating a mixed vaccine to cover both Delta and Omicron, as is customary with influenza.

Another study on Omicron revealed that this new strain seems to replicate more proficiently in the upper respiratory tract and bronchus, but less well in lung tissue, which would explain the lower severity and higher transmission at least partially. To me, this finding ties things together with a plausible reason why vaccinated people (or asymptomatic carriers for that matter) are still able to transmit the virus despite being well protected against disease: upon infection, the virus enters the body through the nose and throat and starts replicating in the mucus. The immune response kicks in only when the virus tries to spread through the blood to the rest of the body, but the person can still shed viral particles from the nose, thus infecting people around them. And that’s why it is still good practice to continue wearing masks after getting vaccinated…

In retrospect, the decision back in May to drop mask requirements in the US appears rather misguided, a consequence of the excitement over the availability of vaccines while ignoring how vast numbers were still resisting vaccination and the possibility of further mutations. It seems to me that Omicron spread fastest in countries with few other mitigation measures: the US and UK, Denmark, which also declared the pandemic ‘over’ a couple of months ago.

The US CDC doubled down on controversial decisions by recommending reducing the isolation period for infected people from 10 to 5 days with little scientific basis, seemingly to push people to return to work sooner… That guideline became the butt of Twitter jokes for a couple of days, but sadly in the real-world effect it may well result in vastly more infections, suffering and deaths. A strain causing less severe disease, but more infectious, can wreck a lot of damage because it will infect more people faster, so it has a greater chance to reach vulnerable people – and to mutate further into possibly more aggressive varieties. Combined with Omicrons increased immune escape, some of the vaccinated will likely be infected as well and may require medical attention. And let’s not forget the prospect of long-term health issues induced or exacerbated by COVID – an aspect that many in the press and in positions of authority conveniently ignore when evaluating restrictions and mitigations, in favor of talking about the short-term economic impact.

I am baffled at CDC’s decision to shorten isolation. Here are tests from the same person: day 0 (3 days after exposure) and day 8. The person still has a huge amount of virus in their nose 8 days after testing positive. n=59. Quickest clearance 6 days, longest (vacc) 8.5 days. pic.twitter.com/yKuXG4NwUO

— Erin Bromage Ph.D. (@ErinBromage) December 27, 2021

Another topic heavily debated on Twitter were rapid tests and whether they work to detect Omicron infections. Some experts insisted they still work, but studies showed their failure rates are higher with Omicron. I personally haven’t put much faith in rapid testing due to their higher false readings compared to PCR tests, and the fact that we’re relying on people with no prior medical experience to perform correct swabs for the test to work. Some of the discussion on Twitter revolved around whether you should swab both the nose and the throat, despite some test kits advising only a nose swab, and I was perplexed by the amount of confusion and conflicting information. Much clearer to advise people to isolate after a possible exposure and wait for a proper test result – or to wear masks around strangers!

We were told all last year how insidiously dangerous asymptomatic carriers were now suddenly when Dems need a strong economy to run on in 2022 because they've accomplished nothing it's no longer an issue. Die for the DOW baby. https://t.co/98hy3BL8VZ

— jordan (@JordanUhl) December 30, 2021

To end on some positive developments, over the past months two antiviral medications against COVID have been cleared in the US, and a new vaccine from Novavax in the EU and other regions. Antiviral drugs could certainly save many lives and alleviate some of the load on health systems from unvaccinated people, although they need to be administered fairly soon after infection, and the supply will obviously be constrained in the short term. The Merck drug Molnupiravir unfortunately has a low efficacy of around 30%, but Pfizer’s Paxlovid had much higher success, cutting the risk of hospitalization or death by 89%.

Post a Comment