After the Cold War, Western elites concluded that realism was no longer relevant and liberal ideals should guide foreign-policy conduct. As the Harvard University professor Stanley Hoffmann told Thomas Friedman of the New York Times in 1993, realism is “utter nonsense today”. U.S. and European officials believed that liberal democracy, open markets, the rule of law, and other liberal values were spreading like wildfire and a global liberal order lay within reach. They assumed, as then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton put it in 1992, that the cynical calculus of pure power politics

had no place in the modern world and an emerging liberal order would yield many decades of democratic peace. Instead of competing for power and security, the world’s nations would concentrate on getting rich in an increasingly open, harmonious, rules-based liberal order, one shaped and guarded by the benevolent power of the United States.

The next misstep was the Bush administration’s decision to nominate Georgia and Ukraine for NATO membership at the 2008 Bucharest Summit. Former U.S. National Security Council official Fiona Hill recently revealed that the U.S. intelligence community opposed this step but then-U.S. President George W. Bush ignored its objections for reasons that have never been fully explained. The timing of the move was especially odd because neither Ukraine nor Georgia was close to meeting the criteria for membership in 2008 and other NATO members opposed including them. The result was an uneasy, British-brokered compromise where NATO declared that both states would eventually join but did not say when. As political scientist Samuel Charap correctly stated: [T]his declaration was the worst of all worlds. It provided no increased security to Ukraine and Georgia, but reinforced Moscow’s view that NATO was set on incorporating them.

No wonder former U.S. ambassador to NATO Ivo Daalder described the 2008 decision as NATO’s “cardinal sin”.

Stephen M. WaltThe recent buildup of tensions on the Ukrainian border have served as a crash course on history and geopolitics. On one side a menacing Russia, massing up troops and threatening to stop the gas supply to Europe, on the other the NATO alliance and a couple of other aligned countries, standing up for Ukraine’s right of self-determination.

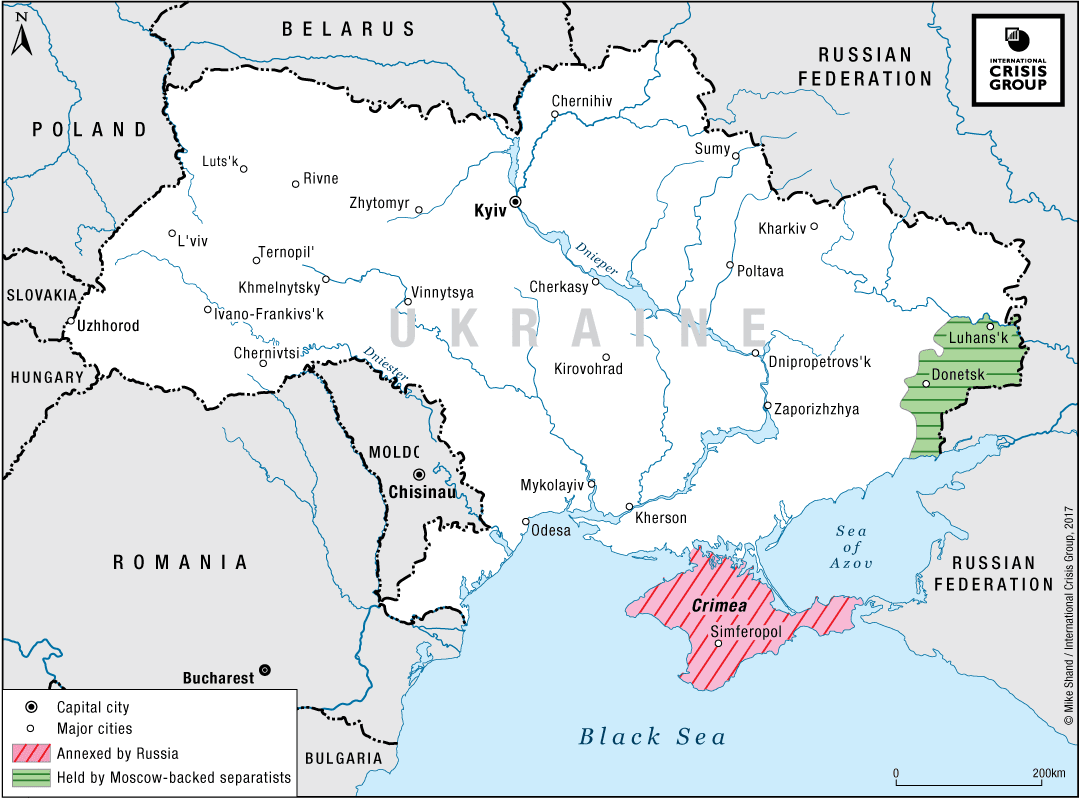

Well, that’s the official angle anyway. In a broader context, Ukraine’s territorial integrity has been compromised in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea, and subsequent sanctions have done little to deter Putin from coming back for more. Since the country is not a NATO member, it’s highly unlikely that the US would intervene militarily to counter a new Russian aggression this time around. And the US’ moral standing for defending the international order has pretty much gone up in smoke when they preemptively invaded Afghanistan and Iraq 20 years ago. There are many complex factors in play and I will try to explore some of them below.

Why Ukraine? Something that is generally left out in the online coverage is that before the Euromaidan protests, so not that long ago, Ukraine’s position was relatively neutral between Russia and the West, with some governments leaning heavily on Russia’s side. As some remarked, the only countries that Russia invaded since the end of the Cold War are… Georgia and Ukraine, and both happened after President Bush offered to include them in NATO. Other interventions, from Belarus to Kazakhstan to Syria, happened unter the pretext that Russia was ‘invited’ in by the standing government.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a weakened Russia was somewhat content with the semblance of a sphere of influence, serving as a buffer against the expanding liberal West. With Putin consolidating power and this buffer growing smaller by the year, a conflict was bound to happen. It’s not so much about Putin trying to turn back the course of history, as some tried to frame his actions, but about carving more influence for Russia, a world order where its power is acknowledged – even feared.

Why now? A full-scale invasion could have been a lot simpler during the Trump presidency, who would have likely put up very little resistance to a Russian advance on the front. Well, yes, but this assumes Putin intends to invade and keep Ukraine, which would prove costly in the long term because of local resistance and further sanctions, with little apparent upside. His goals could be different, more along the lines of obtaining a solid pact with the US over the scope of NATO in Europe and its military involvement. That would have been difficult to achieve under Trump, as European countries would have vehemently opposed any deal between Trump and Putin, and the next US president could have easily reneged on it citing Trump’s ties to Russia.

A possible peaceful de-escalation to this conflict would be for Ukraine to declare itself neutral once again from both NATO and Russia – but unfortunately there is no guarantee that Russia would either accept this resolution or respect it in the future.

My personal impression is that Putin is secretly enjoying watching the West’s worries over Russian troop deployments and the attention he receives as a result. From his exaggerated demands during diplomatic exchanges, one might get the idea that he doesn’t take these talks all that seriously, or that his intentions are quite different and yet unstated. This remains in fact the central challenge for diplomacy: revealing Putin’s usually inscrutable aims in order to formulate a proper response.

Only one question matters : what is Putin looking for? If he wants some guarantees on the enlargement of NATO or on the deployment of US missiles, a compromise is possible. If he wants to undermine the geopolitical status quo, pushing him back is the only conceivable policy. https://t.co/uOfOMAJrJL

— Gérard Araud (@GerardAraud) January 24, 2022

Some have argued that continuing negotiations are giving Ukraine more time to prepare for an incursion, at the same time increasing the costs for Russia to station troops at its border. The same logic applies the other way around though: perhaps Putin is using the overt threat of military action as a diversion from his actual plan, which may involve destabilizing Ukraine (through cyberattacks, fomenting popular unrest via disinformation and reducing their gas supplies), to pave the way for a softer takeover of its government. Or perhaps he is biding his time until the media attention wanes and other challenges in Western countries take precedence over what will start to look like a manageable standoff. Then, when nobody’s watching this situation anymore, maybe during the summer months with most people and decision makers blissfully on vacation, he would strike swiftly before anyone has a chance to react.

Moscow itself may not yet have decided whether or not to escalate, when and to what extent. It may want to see how events unfold in response to its troop build-up and keep its options open as long as possible. The Kremlin may also think that time is on its side, and that a sustained atmosphere of tension over the course of weeks or months will, in and of itself, encourage Kyiv, Washington and European capitals to make concessions.

Ukraine and its Western partners are, however, in no mood to offer major compromises on the Minsk process or NATO and now, in response to intimidation, is not the time for them to do so. Even were they to seek some form of accommodation, they would risk Russia simply pressing for more. Moscow would likely understand its victory both as a Western recognition of its rightful role vis-à-vis Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries and as an affirmation of the benefits of threatening and using military force to attain its goals. Nor is there any guarantee that Moscow would feel sufficiently secure as a result of such a settlement to curtail its aggressive behaviour, particularly if tensions persist in the Black and Baltic Sea regions and elsewhere.

Crisis Group Europe Briefing N°92

At some level, this moment feels reminiscent of the build-up to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Just like back then, US sources are flooding the airwaves with alarmist intelligence assessments (about chemical weapons that were never discovered), with the UK mimicking their position like a faithful lapdog in search of global relevance. Other European countries have been more skeptical of this alleged high threat level and not keen to get into a confrontation with a large and bad-tempered neighbor – and for good reason, as we will bear the brunt of the consequences in the event of a military conflict, in terms of refugees and reduced trade because of sanctions aimed at Russia. Even the Ukrainian government is treating this more like business as usual, possibly to prevent popular panic.

It seems to me that both the US and UK are exploiting this situation, at least partially, to divert attention from internal issues, from inflation to their abysmal handling of the pandemic – a tactic they frequently accuse Putin of pursuing. I wonder if some of this US saber-rattling is not meant to bring Europeans back in line with US foreign policy, maybe to push Germany to scrap the gas pipeline Nord Stream 2, an objective that the US never achieved until now. As a side benefit, I’m sure that US businesses would be thrilled to replace that Russian supply to Europe with shipments of US liquified gas.

The initiatives to send weapons to Ukraine, cheered on loudly by the media, seem somewhat misguided to me. Experts have estimated that the Russian military has an overwhelming advantage, despite these late additions to Ukrainian arsenal. The recent mobilization of under 10.000 US soldiers to Eastern Europe looks pitiful when compared to a Russian force of over 100.000. Besides, actively supplying weapons, even purely defensive ones, to a party in the conflict, would seem to undermine diplomatic talks.

All this push to arm Ukraine seems to conveniently discard last year’s lesson of Afghanistan, who had an army fully equipped by years of American occupation, but no willingness to fight, so it folded when the Taliban rolled in. While Ukraine overtly is willing to resist a Russian invasion, I wouldn’t rule out that the government, faced with the prospect of a bloody conflict (and with the proper bribes and coercion from Russia), could cave just as easily, but maybe in a less public fashion and over a longer period. For this scenario we have the examples of Poland and Hungary, who turned autocratic despite being EU and NATO members – what’s stopping Ukraine from going down the same path and embracing Russia again, under the guise of democracy?

A yet more delicate conversation that Washington should have with Moscow concerns the range of contingent costs and risks that might or might not be imposed, but that will become an increasingly real possibility if tensions continue to escalate. Directly relevant to the prospect of an eastern buildup is the prospect that some NATO states might themselves intervene in any conflict in Ukraine. While most member state governments will be unwilling to take such steps, some – perhaps including those of Poland and the Baltic states that sit on NATO’s eastern flank – may feel they must, especially if fighting drags on.

That would be dangerous indeed. NATO allies are not bound under the Atlantic Treaty to follow a handful of member states onto the battlefield in Ukraine, but if their presence there touches off a conflict that reaches their territory, then the alliance might well feel it needs to come to their defence.

Crisis Group Europe Briefing N°92

As someone living close to the heat of the action, I would like nothing more than the tensions to cool off quickly and without fighting, as I fear things could quickly get out of control. As tensions continue, I think the gravest danger comes from rogue attacks, either military or in cyberspace, that could trigger a disproportionate response from either side.

Post a Comment