In the sense that an escalation of conflict between Russia and the West helps divert U.S. attention from China, China should rejoice with and even support Putin, but only if Russia does not fall. Being in the same boat with Putin will impact China should he lose power. Unless Putin can secure victory with China’s backing, a prospect which looks bleak at the moment, China does not have the clout to back Russia. The law of international politics says that there are “no eternal allies nor perpetual enemies”, but “our interests are eternal and perpetual”. Under current international circumstances, China can only proceed by safeguarding its own best interests, choosing the lesser of two evils, and unloading the burden of Russia as soon as possible.

A just cause attracts much support; an unjust one finds little. If Russia instigates a world war or even a nuclear war, it will surely risk the world’s turmoil. To demonstrate China’s role as a responsible major power, China not only cannot stand with Putin, but also should take concrete actions to prevent Putin’s possible adventures. China is the only country in the world with this capability, and it must give full play to this unique advantage. Putin’s departure from China’s support will most likely end the war, or at least not dare to escalate the war. As a result, China will surely win widespread international praise for maintaining world peace, which may help China prevent isolation but also find an opportunity to improve its relations with the United States and the West.

Hu Wei

A clear and concise argument against Chinese support for Putin, but I fear that we are overestimating the weight of rational arguments in foreign policy – after all, a full-scale invasion of another country is hardly rational in terms of costs vs. benefits. Indeed, other channels support the ‘no-limit partnership’ with Russia for its supplies of energy, food and other raw materials, and to potentially rely on Russia’s nuclear arsenal as deterrence in the event of a conventional war with the US in the South China Sea. Publicly China has declined to ‘take sides’, which roughly translates into tacit support for Putin. A position that resulted in a frosty atmosphere at a recent EU-China summit and that is unlikely to change substantially in favor of Western interests.

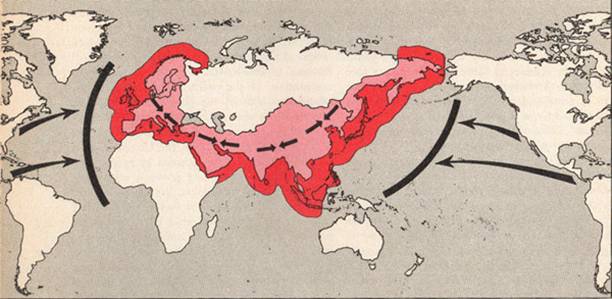

The alignment between China and Russia in the current conflict reminded me of a short article about geopolitics I have read some time ago, discussing the role of geography in shaping relations in Eurasia and the wider world. It too advised the US to leverage Russia as counterbalance to a rising China – obviously too late for that strategy. Instead, China is now seeking to leverage Russia as a distraction against the US as it’s amassing strength both economically and militarily.

Those who counsel engagement with China would do well to reflect on what Spykman wrote in The Geography of the Peace about the nature of the international system:

[S]tates [that] have very different sets of values which they each regard as fundamental and, with all the goodwill in the world, … will not avoid conflict over the applications of these values; nor will they refuse to apply pressure for the attainment of what they consider justifiable ends… At any given time, there are always some [states] that are satisfied and others that are dissatisfied with the political and territorial status quo. When such dissatisfaction reaches a certain point, efforts will be made to change the situation by force. A spirit of co-operation and forbearance is no defense against a determined seeker of change.

This is a remarkable description of what scholars today call the Thucydides Trap. The wisdom of The Geography of the Peace is timeless.

Francis P. Sempa

Post a Comment