Since the end of World War II, the number of armed conflicts between states has plummeted. One group of countries, however, stands out in its continued aggression: oil-rich states, which have been at the heart of some of the most notorious and bloody conflicts in recent decades, from the Iran-Iraq War to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, from the Syrian civil war to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. No matter how you define a petrostate—whether you look at a state’s oil-derived wealth, its dependence on oil revenues, or its exports and relative importance to world markets—there is strong evidence that petrostates are more likely than other countries to start wars.

The question of why is trickier. The simplest explanation is wealth. Oil-wealthy states—which enjoy substantial income from their production of oil and natural gas—are in a lucrative business, one typically dominated by states themselves, which earn billions of dollars from the oil trade. From weapons to foreign aid to violent proxies, leaders of oil-wealthy states simply do not need to make the same budgetary trade-offs as non-resource-wealthy states.

This offers one potential explanation for oil-wealthy states’ tendency toward conflict: Their overconfident leaders mistake high military spending for actual capability. It also suggests an unfortunate corollary: Oil-wealthy states not only are more likely to start wars but may be more likely to lose them. Oil wealth may even cushion the negative impact of losing a war, providing ways to buy off segments of society and allowing a leader to maintain power despite repeated conflict losses.

Emma Ashford

Interesting analysis, and especially timely, considering the economic war between Russia as a large oil and gas supplier and the rest of Europe.

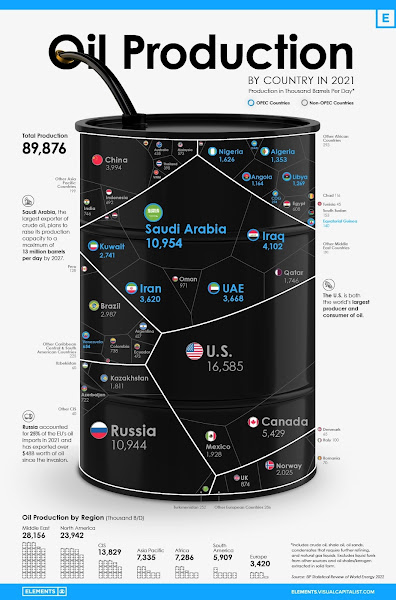

Conspicuously absent: the role of the United States, which over the years intervened numerous times to secure its own access to oil supplies. Just a couple of days ago Twitter popped up into my timeline the anniversary of the 1953 coup to depose Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, orchestrated by the US and Britain to prevent the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry – no wonder that Iranian leaders foster a deep distrust of the United Stated to this day. The continued US involvement in the Middle East can be tied to a large extent to defending its own access to oil reserves in the region (including Biden’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia).

Over the past years though, the US steadily increased its oil output and exports, to the point it became a net exporter after 2020. It will certainly be interesting to follow how US foreign policy shifts as a result of this change, and as the importance of fossil fuels for energy security (hopefully) decreases over the coming decades.

Post a Comment