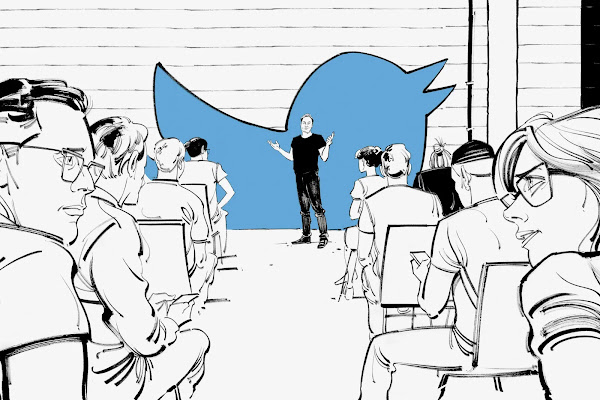

On Musk’s first full day in charge, October 28, the executive assistants sent Twitter engineers a Slack message at the behest of the Goons: The boss wanted to see their code. Employees were instructed to

print out 50 pages of code you’ve done in the last 30 daysand get ready to show it to Musk in person. Panicked engineers started hunting around the office for printers. Many of the devices weren’t functional, having sat unused for two years during the pandemic. Eventually, a group of executive assistants offered to print some engineers’ code for them if they would send the file as a PDF.Within a couple of hours, the Goons’ assistants sent out a new missive to the team:

Zoë Schiffer, Casey Newton, Alex HeathUPDATE: Stop printing, it read.Please be ready to show your recent code (within last 30-60 preferably) on your computer. If you have already printed, please shred in the bins on SF-Tenth. Thank you!

So much has happened since Elon Musk begrudgingly took over Twitter that one could almost draft a novel just by citing story headlines. I had intended to compile a list of them as a blog post, but I gave up as they kept piling on with no end in sight. Even as the agitation settled down somewhat after six months or so, the stream of failures and foolish ideas from Musk never stopped. Instead, I will focus on my two main conclusions from this utterly pointless and fully preventable fiasco – though I’m not certain these count as separate, as they both relate to the prevailing narratives in the media and how they distort perceptions and ultimately cloud underlying facts.

For years we kept hearing criticisms from journalists that Twitter is badly run, that top management doesn’t use the platform as much as their power users, that the company doesn’t ship features fast enough to compete with Facebook, that this and that moderation decision was wrong or hasty. The post-Musk mess has certainly put this into a whole new perspective: in comes a new manager who is possibly the heaviest Twitter user around but is clueless about the engineering and community aspects of running the platform, and arrogant enough to think he has a magic fix for everything. The results speak for themselves…

Perhaps the media was too quick to judge previous Twitter management; perhaps there’s no obvious solution for moderation or scale, so the cautious approaches before Musk were just right to maintain Twitter’s unique culture and outsized influence.

Alicia knew Twitter had problems; when prospective employees asked her why she’d stayed there so long, she would tell them, honestly, that the company was incredibly inefficient. It took a long time to get buy-in on projects, and communication across teams was generally poor. But it operated with a “benevolent anarchy” through which anyone could influence the direction of the product.

You didn’t need someone in a position of power to explicitly grant you permission, Alicia says.It was very much a bottom-up organization.

On a related note, pundits could never shut up about Jack Dorsey’s dual role as CEO of Twitter and Square, complaining that it didn’t leave him enough time to focus on Twitter, while praising Musk for essentially the same thing! Never mind that Musk at some point was launching companies left and right and nobody bothered to question his plans and availability for these endeavors.

Twitter’s trust and safety team compiled a seven-page document outlining the dangers associated with paid verification. What would stop people from impersonating politicians or brands? They ranked the risk a “P0”, the highest possible. But Musk and his team refused to take any recommendations that would delay the launch.

Twitter Blue’s paid verification system was unveiled on November 5. Almost immediately, fake verified accounts flooded the platform. An image of Mario giving the middle finger from what looked like the official Nintendo account stayed up for more than a day. An account masquerading as the drug manufacturer Eli Lilly tweeted that insulin would now be free; company executives begged Twitter to take down the tweet. The marketing team tried to do damage control.

You build trust by being transparent, predictable, and thoughtful, one former employee says.We were none of those with this launch.

Which brings me to my second point, which is that so much of tech journalism is just recycling companies’ press releases and fawning over founders hoping to get a scoop or an interview, a fleeting moment of fame for clicks and ad impressions. This is how you get a constant stream of acclaim for Musk despite all his dumb and hostile decisions, both before and after acquiring Twitter, when any objective observer would identify him as a dilettante with too much money, power, and a hyperinflated ego. A prime example of this pernicious access journalism is Kara Swisher, who covered Musk (and countless other tech CEOs) favorably… until he stopped answering her requests because his public profile outgrew the need for her accolades.

The shallowness of tech journalism may explain why many journalists fled Twitter and embraced… a Facebook product of all places, a company that many have criticized before, and with good reason. But if your main drivers are cheap notoriety and ego boosts, it’s only natural to be an early adopter in the hopes of capturing the audience on a new social network.

His problem — his insurmountable, impossible problem — is that while one can buy attention, one cannot buy approval. Musk believed that by buying Twitter he would show everybody exactly how smart, interesting and funny he was, without stopping to consider whether any of that was true. And I believe that deep down he realizes that the people that love him do so for an extremely hollow reason — that he’s rich and powerful. Musk is aware that his fans are toadies — mewling sycophants and fellow reactionary goblins that are only loyal to what Musk symbolizes. These aren’t people that he’s earned the respect of. He got it by default because they respect anyone loud, rude and rich.

Ed Zitron

The irony of the situation is that Twitter is still limping along, despite multiple predictions of impending doom and a massive exodus of advertisers and users. For me, it remains a much better source of news and analysis than Threads or Bluesky. Granted, I haven’t taken the time to set up my following graph on either of these new networks, but from my anecdotal experience, the engagement on popular posts is an order of magnitude higher on Twitter than on Threads or Bluesky. I’m not sure either can recapture the spirit of Twitter; Threads is constantly hampered by its ties to Instagram and Meta’s reluctance to let it develop independently, and Bluesky seems too niche at the moment, with too few people of real importance active there.

Post a Comment