The struggle for Russian hearts and minds is one that must be waged primarily by Russians themselves. Mr Putin is attempting to rally support with the argument that the entire West is fighting Russia, and that it holds Russians in contempt and wants to destroy their country. The West counters that its argument is with Mr Putin and his regime, not the Russian people. It does not want the destruction of Russia, but for Mr Putin to leave Ukraine to determine its own future as a sovereign nation.

If Europe shuts its borders to all Russians, it is handing Mr Putin tangible evidence that he is right. It undermines Europe’s credibility as a defender of human rights and alienates those parts of Russian society whose interests and values are most strongly aligned with the European Union and Ukraine. It is also failing to shelter the people best suited to rebuild the Russian state once he is gone. Just as it did in the cold war, the West should offer safe haven to the Russians with whom it has no argument.

If the exodus of draftable Russians continues, Mr Putin may decide to impose his own travel ban on them. In other words, the man who called the collapse of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century may partly recreate the Iron Curtain. Now, as then, the West should let the tyrant in Moscow take the blame for restricting Russians’ freedom, and welcome the brave souls who escape.

The Economist

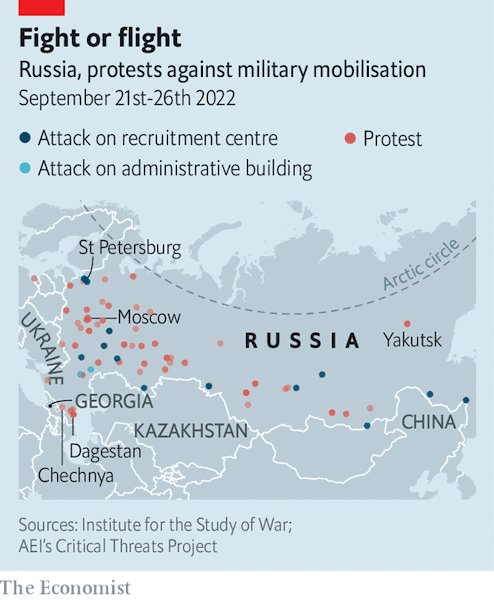

The recent mobilization orders in Russia have sparked another round of furious debate, this time over the rising numbers of Russians fleeing the country to avoid being drafted. European countries bordering Russia have rushed to close their borders and prevent their entry. As many, including the article above, pointed out, a blanket ban against Russian citizens is against Schengen rules and violates the right to asylum, has little strategic justification, and fuels Putin’s narrative that the West is targeting Russians as a whole, rather than Putin’s regime specifically.

The arguments from the leaders of the Baltic states and Finland are illogical to say the least. Holding individuals responsible for the policies and actions of their government is a fraught proposition even in functioning democracies, regularly holding free elections. A lot of citizens aren’t too politically engaged, don’t vote regularly or support the opposition – would it be fair to hold them accountable for a government they didn’t elect? That applies even more to people living under autocracies, where their options for electing people in power are severely limited and every act of disapproval or protest can have immediate and grave consequences for their personal safety.

Could forcing Russians fleeing mobilization to go back to Russia foment revolution? Maybe. But I wouldn't count on it, and in the meantime, I'd look for ways to limit the war machine and be humane towards those fleeing it. A 🧵. 1/18

— Olya Oliker aka Dr. Olga Oliker (she/her) (@OlyaOliker) September 27, 2022

Telling people to return home and fight their oppressive rulers is cruel and heartless; by that logic no country would ever accept political asylum seekers. I find even the fear of security threats from incoming Russians to be overstated and implausible. If Putin wanted to infiltrate neighboring countries, he could have done so long ago, when the EU visa process was more permissive for Russian citizens, not wait until now, when tensions are high and any traveler will likely be subjected to increased scrutiny. Covert agents could simply use false identities, concealing their connection to Russia, or attack and plant misinformation remotely through cyberattacks – no need to hide them among draft dodgers.

The bigger issue with shunning these people though is the lasting impression it may leave on them: when they most needed a helping hand, the West shut its gates to them and sent them back into Putin’s grip. When the Russian leadership eventually changes, people will likely remember this moment and they will be less inclined to support liberal, European-oriented parties, turning to nationalist and isolationist movements instead. And this in turn will make it more difficult to achieve reconciliation and lasting peace on the continent.

I can certainly understand people in the Baltic states being uncomfortable with a large influx of Russian men, given their history of occupation – I would probably be as well. But that’s no excuse for their leaders to further stoke Russophobia and make irresponsible strategic decisions. It’s an unfortunate shortcoming of democracies in this age of social media that many politicians govern for likes and their vocal social media crowd, instead of choosing more challenging paths in the long term interest of their country and allies.

Post a Comment