While the attention of the public and authorities has been thoroughly captured by the Russian invasion of Ukraine over the past weeks, and despite massive efforts to diminish the issue in public eyes, the two-year-old pandemic is far from being a thing of the past. As I feared in my previous article, case numbers have skyrocketed here in Romania throughout January, reaching an official daily high over 40,000 on February 1st, a new record. Like other Omicron waves around the world, the sharp increase was followed by a quick retreat, with new cases declining at a rate of about 35% each week. Currently, in the second week of March, the case numbers hover above 3,000 daily on average.

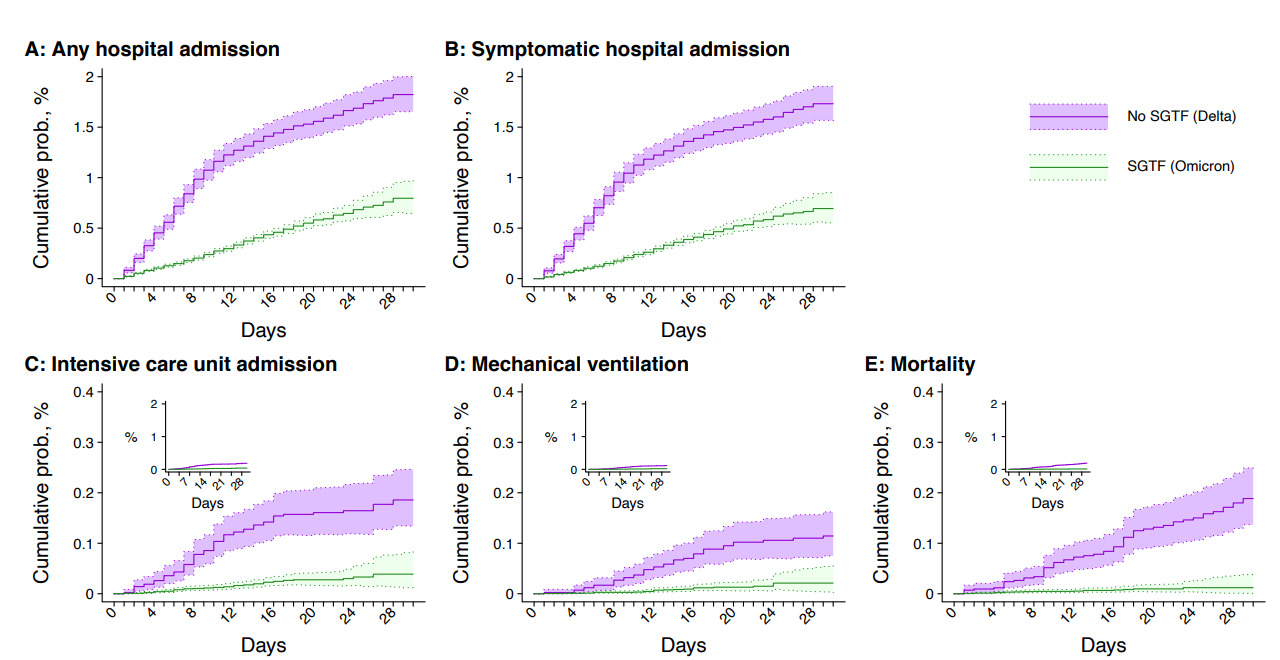

Mortality has also progressed on a trajectory similar to other Omicron waves: deaths have increased after the typical two-week delay, but at a much lower rate than cases – on average 35% per week compared to almost 90% for cases. The number of daily deaths surpassed 200 on two occasions in the second half of February, considerably lower than the mortality of the autumn Delta wave, which reached as high as 600 a day. Deaths are also currently in decline, although, again, at a lower rate than cases, around 20% per week. Our experience seems to support conclusions from other countries that the Omicron mutation causes less severe disease, at least in populations with sufficient prior immunity, either through infection or vaccinations. But during this wave, medical personnel also had access to new antiviral medication for severe COVID cases, so this might have also contributed to keeping the death rate lower than before.

Other signals are less reassuring though. As mentioned above, deaths are declining slower than cases, possibly indicating that disease caused by Omicron evolves over a longer timespan after the onset of symptoms.

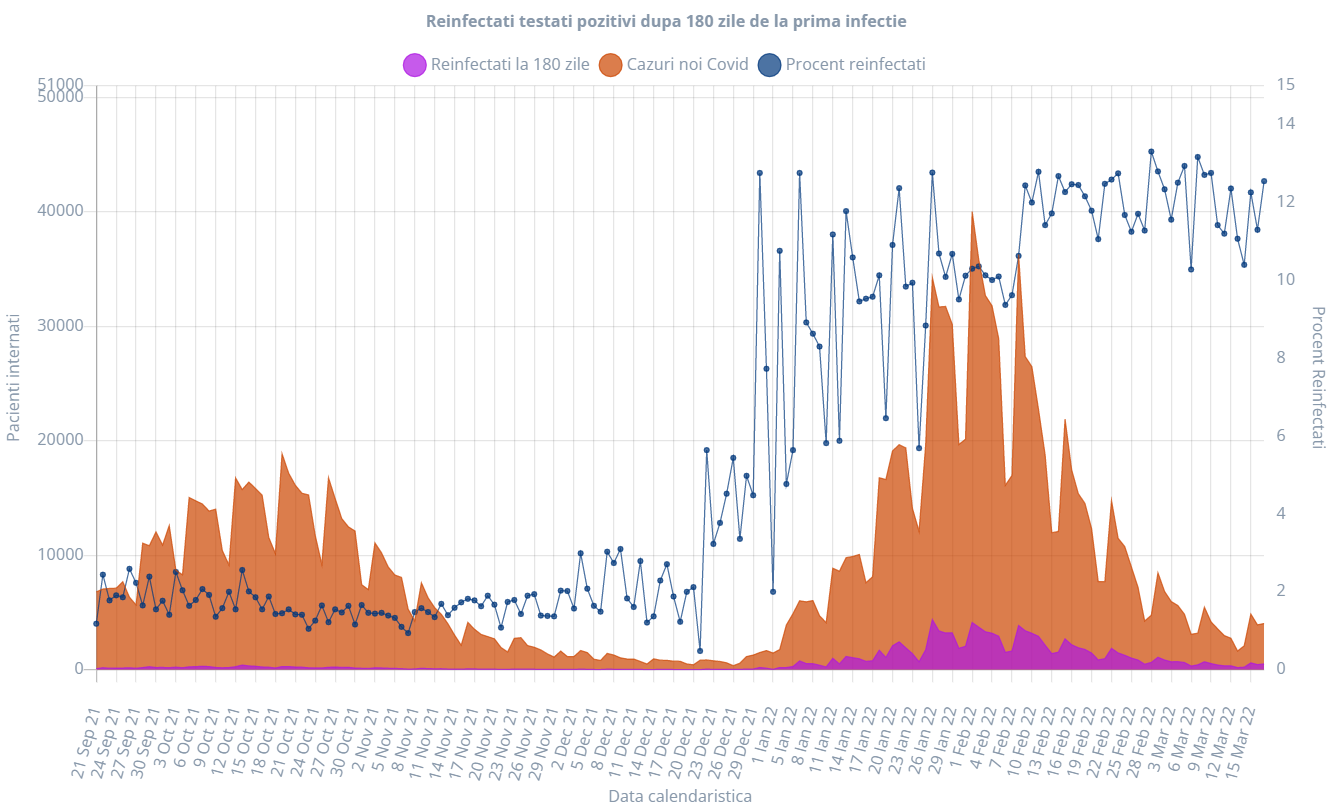

Starting with September 2021, health authorities have started publishing data about reinfections, defined as people testing positive a second time 180 days or more after a prior infection (this interval was recently shortened to 90 days). During the Delta wave last year, the reinfection rate remained steady at 2% or lower, meaning that most people who recovered from the disease were reasonably well protected from another infection. In the second half of December though, the reinfection rate begun climbing until it stabilized at 10–12% in January, where it remains to this day. As studies pointed out, Omicron may cause milder symptoms, but it can more easily evade immunity, thus making it more likely that people will become infected repeatedly in the absence of other measures to reduce spread. The reinfection rate may prove a valuable tool to predict the emergence of new variants, provided authorities will keep measuring and publishing this data.

A similar dynamic occurred with the percentage of vaccinated patients that died: during the Delta wave, vaccinated people generally made up less than 10% of total deaths. After the onset of Omicron, that percentage climbed above 10%, reaching as high as 22% at the height of the wave in early February – likely a combination of waning immunity and reduced effectiveness of vaccines against Omicron. It’s interesting to note that the percentage of deaths among vaccinated is slightly larger when case numbers are high, and getting lower when incidence declines, possibly showing how important it is to keep viral spread as low as possible to protect the entire population – including those with underlying conditions making them more vulnerable, vaccinated or not.

Speaking of vaccinations… well, it’s not worth speaking of them, as the numbers have only gone down in past months. The overall vaccination rate in Romania remains low at around 40%, and of them around 40% have received their booster dose – not encouraging in case a second booster will be recommended. I noticed with concern that the usual sources regularly publishing data have even stopped providing updates on vaccinations on March 13th.

there's a serial killer terrorizing the city but he only murders old people and sick people so we don't need to worry or try to stop him

— the hype (@TheHyyyype) January 9, 2022

In this ambivalent context, Romanian authorities have nevertheless decided to drop most existing protective measures after March 8th: mask are no longer required in indoor spaces or public transportation, merely recommended (which of course prompted many people to ditch them entirely); vaccination certificates are no longer required in malls and large venues and vaccination was moved to the responsibility of family physicians (expect even fewer people to get vaccines from now on); no restrictions on the number of people attending events and no more quarantines; local health authorities are no longer providing at-home PCR tests (expect testing, and with it the quality of data about infections, to drop significantly).

The principal factor driving this hasty decision seemed to be… that most other Western countries are dropping mitigation measures left and right, and we didn’t want to be left behind. Denmark was among the first to renounce all measures – and was ‘rewarded’ with increased deaths, despite manageable hospital load. France is dropping vaccination certificates, the UK is eliminating free testing and reducing the vaccination drive, and so on. As a result, cases are again on the rise in most countries in Western Europe. Similarly, the US made masks optional, but recommended, and is pushing people to return to the offices, despite increasing gas prices – an unwise decision for multiple reasons, especially since wastewater analysis indicates yet another imminent increase in cases. Unfortunately, the current US administration seems most focused on the appearance of normality and getting economic indicators back on track, at the expense of individuals’ wellbeing, and other countries are blindly following their example.

telling people to take off their masks and go back to their shared open workspaces is exactly what I would do if I were a rapidly mutating airborne virus

— Brianne Benness (@bennessb) March 7, 2022

On top of that, several Asian countries are battling fresh resurgences of the virus, from Hong Kong to South Korea to New Zealand, beyond anything they previously experienced these past two years. Omicron may not be that mild after all when it spreads through a population who used less effective vaccines and failed to vaccinate the majority of elders, such as Hong Kong. The recent lockdowns in key Chinese manufacturing and trading hubs threaten new shocks to supply chains and inflation.

Needless to say, I am very wary of how things will unfold over the next weeks and months, perhaps even more so than two years ago at the start of the pandemic. Lifting mitigation measures coincided with the influx of Ukrainian refugees, which I’m pretty sure nobody bothered to screen for coronavirus infections or to prompt to wear masks. Maybe a minor concern for people fleeing a war, but you certainly don’t want to be sick on top of that. This past weekend Bucharest also hosted a large concert to gather funds for refugees, already without any preventive measures in place. Universities asked students to return to full-time in-person courses basically immediately, a decision that angered many who were happy studying from their home cities, without paying expensive rents in large cities and exposing themselves to the virus. I expect case loads to start rising again soon – in fact, today’s reported figure is already 500 cases higher than a week ago, the first week-on-week increase in some time. This many well be reporting backlog, but also the early signs of a new wave.

Der Vorteil von nicht-pharmazeutischen Massnahmen (Luftfilter, CO2-Messung, Masken, Homeoffice, kleinere Schulklassen etc)? Sind bei jeder #SARSCoV2 #COVID19 #Variante, auch zukünftigen, wirksam. Impfung, Medikamente, selbst Diagnostik muss erst geprüft & ggfs. angepasst werden.

— Isabella Eckerle (@EckerleIsabella) February 19, 2022

I will continue to wear masks inside stores and public transportation, but that won’t help that much to contain community spread, if many people neglect to do the same. Between less testing, no travel restrictions, and masks no longer being mandatory, we, both here in Romania and across Europe and North America, are creating the perfect conditions for future surges to catch us completely off guard, this time not because we were unprepared, but because we have simply given up the fight and refuse to consistently use the tools at our disposal…

"living with cholera" meant changing the sewage system in every city in the world.

— Michael “oplopanax” Coyle (@lithohedron) March 13, 2022

If you think "living with COVID" means pretending it doesn't exist, I've got some bad news.

The apparent mildness of Omicron has lulled many decision-makers into complacency, embracing wishful thinking that this would be the last serious wave, that no new more severe variants would emerge, that we can go back to pre-pandemic ‘normal’. Neither of these assumptions hold up to the scrutiny of experts, who have repeatedly warned that viral mutation is random, so the emergence of more severe or immunity-evading variants is perfectly plausible, and that ‘endemic’ status for a dangerous virus means applying targeted measures to keep its spread in check and protect vulnerable people, not denying its existence and downplaying the hazards.

Under these circumstances, the most likely scenario in my opinion is recurring ‘flash floods’ of infections, possibly with slightly altered strains each time, coupled with spikes in hospitalizations and mortality. Unlike influenza, which usually causes one wave each year during the cold season, this coronavirus seems perfectly capable of triggering multiple waves each year. Are we content to live with two or three surges at random intervals throughout the year in the absence of mitigating measures? Even if the situation stabilizes at current levels in Romania – and there is no reason to believe that it would – that would translate to 9,000 to 25,000 additional deaths yearly, a 3–9% permanent increase on Romania’s pre-pandemic death toll.

Imagine if gov’ts & PH said, “There’s less lung cancer now, so let’s allow indoor public smoking again. Smokers have freedoms too.”

— Jennifer Heighton (@jheighton3) March 6, 2022

Or “There are less car accidents now & designated drivers are inconvenient. Only a few victims will die anyway. Let’s allow drinking & driving.”

More worrisome still are studies showing the long-term health side effects of coronavirus infections, from accelerated aging of the brain to increased incidence of heart disease and vascular issues. Letting the virus freely infect most of the population will result not only in increased mortality, but increased disability and chronic sickness for many people as well. Waning immunity and new variants will all but ensure that people will get infected repeatedly, each time with worse results for their health. Another troublesome wildcard is how the virus can infect and spread through animals, both wildlife and domestic; this additional reservoir could yield new highly mutated variants and reintroduce the virus in areas where it was previously eradicated. It somehow feels like we’re sliding away from finding a positive solution to this crisis, towards a painful, yet publicly ignored, compromise.

Post a Comment