What does it mean to say Thucydides was a realist? It is to say that he was one of the founders of a pessimistic intellectual tradition that believes the world, like the one he endured, is inherently a cold, harsh, dangerous place in which power and its acquisition is paramount. In this world, interests diverge and clash, and cooperation is bound to be impermanent. There is no reliable authority above the fray. No-one can be certain of others’ intentions, which can change. This makes for a world of ultimate solitude. Ruthless self-help and prudent self-restraint are both imperative. To survive in it, polities must accept and work within its constraints.

Realism at its core is the capacity to look at the world without euphemism. In that spirit, Thucydides is a tonic to wishful thinking, thereby supplying the intellectual tools to resist fanciful expectations. If there is one source of false hope in our time, leading to ill-preparedness and shock, it is the widespread conceit that the ‘twenty first century’ or ‘Europe’, or something in our contemporary condition, should rule out certain bad things happening.

As we too have discovered, ‘hope is an expensive commodity’. Against earlier expectations that a growing China would supplicate itself to US hegemony, it grabs land, coerces and threatens far and wide, and has embarked on a vast naval and nuclear build-up. Against confident earlier claims that his regime ‘must’ go, Gulf states reconcile themselves to Syrian tyrant Bashar al-Assad’s victory after a civil war of unimaginable terror. And against prophecies that geopolitics is an illusion and that Russia would not dare go further than subversion around the edges, Vladimir Putin has launched his latest aggressive lunge into Ukraine.

Patrick Porter

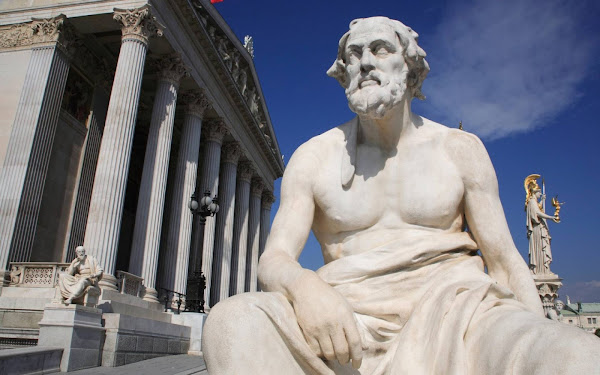

The Greek historian Thucydides was regularly mentioned in a podcast I frequently listen to, and this short recap of his work – and the increasing geopolitical instability – makes me appreciate his insights more. Scholars started applying his history of the Peloponnesian War to the U.S.-China relations in the twenty-first century, a confrontation emerging as a rising power challenges a ruling one.

But many of his other conclusions are just as fitting for our times: the absence of a higher authority regulating international relations (despite its overt role, the United Nation has power on the global stage only insofar member states, and particularly great powers, allow it), the pitfalls of becoming too successful (as the United States suddenly found itself after the collapse of the Soviet Union, leading them to embark on ‘disastrous peripheral wars’ in Afghanistan and Iraq, and wrap itself in illusions that its actions are mainly rooted in principles and morality, not in precise interests), over-reliance on international friendships (as Europe has relied on American security guarantees over decades, becoming vulnerable to aggressive neighbors and an American retreat).

The same principles naturally apply to the war in Ukraine. There’s no shortage of voices loudly proclaiming that Ukraine should be free to do what it wants and end the conflict on its terms. To me, this is the very definition of ‘wishful thinking’; no one is completely free to do what he wants without considering the consequences, least of all nations states. Ukraine and its leadership should instead consider what they can realistically achieve – with or without assistance from the West.

The countries providing aid should also be upfront to themselves and to Ukraine why they are doing this (not for some vague international principles or notions of justice, but because it’s in their own interest to contain Russian aggression) and how much assistance they are willing to provide (enough to fight off the invasion, while avoiding escalation and the use of weapons of mass destruction). This second part seemed more clearly delimited at the beginning of the conflict (no NATO troops in Ukraine, not establishing a no-fly zone), but the lines became increasingly blurred as fighting continued and Ukrainians repealed the Russian advance on Kiev. These early successes may make it appear as if a Ukrainian decisive victory is imminent and cloud their judgement regarding potential negotiations. You obviously want to negotiate from a position of strength, but for that you need to realistically assess when you have maximum momentum in the war. Cheering Ukraine from the sidelines will not help it achieve a good negotiating position; it may well make it discard the right moment, hoping for a better outcome in the future.

The idea that nations can heavily contribute to a war effort without any say in its execution is offensive. Those arming Ukraine may not be risking enough to suit Ukraine, but they aren’t risking nothing — the danger of Russian retaliation remains. And sanctions entail economic pain for those sanctioning as well as the sanctioned.

Moreover, the terms and timing of war-termination will affect NATO countries too, determining the extent and severity of economic blowback, as well as the likelihood of another invasion and resulting crisis. Surely Western leaders have a right — even a responsibility to their constituents — to determine how to use their military aid and economic sanctions in ways that also serve their interests, not just Ukraine’s.

Patrick Porter, Justin Logan & Benjamin H. Friedman

Post a Comment